Young Historian: Lincoln’s Secret Journey

Young Historian: Lincoln’s Secret Journey

March 26, 2025By KELI HOLT

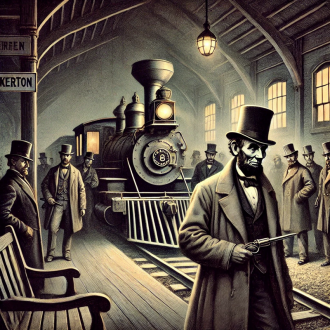

At 3:30 a.m. on Feb. 23, 1861, the 16th president-elect, Abraham Lincoln, stepped off his train from Philadelphia in Baltimore station and immediately boarded a different train heading to Washington, D.C. For the last 12 days, Lincoln had toured the American Midwest and New England, giving hundreds of speeches to enormous crowds of supporters. On the advice of a 12-year-old girl at one of his stops the previously clean-shaven Lincoln began growing his “whiskers” into the famous beard we associate with him today. The Lincoln who switched trains in Baltimore, however, did so in the middle of the night and in disguise. He even swapped out his ubiquitous stovepipe hat, which would make him recognizable to anyone, for a common Kossuth, or slouch, hat on the recommendation of his advisors.

Baltimore was the capital of Maryland, and while Maryland had not joined parts of the south in seceding, or leaving, the union, there were thousands of Southern sympathizers in the border state. Alan Pinkerton, head of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, was charged with protecting the president-elect and he had received word that there were assassins waiting to ambush Lincoln. As Lincoln boarded his overnight transport to the capital, Pinkerton ordered the telegraph lines to be cut so that no one could transmit the president-elect’s location. For many Americans, in both the South and North, Lincoln’s clandestine arrival in D.C. confirmed their worst suspicions: Lincoln was weak and not up to the task of dealing with an America that had torn itself apart.

Lincoln was elected in November 1860 by winning only 39.7% of the popular vote (to this day the lowest percentage by an outright winner). Lincoln won because he carried almost every Northern state, all of which had outlawed slavery. He had campaigned on the promise that he would not end slavery in the states where it already existed (the South) but that he would oppose extending slavery into any of the new states and territories of the American West.

Lincoln’s relatively moderate approach to slavery was still too much for the South, which demanded the right to carry enslaved persons into the new states and territories created by American westward expansion. Many Southern leaders had convinced themselves that it was just a matter of time before the more heavily populated and more economically prosperous North would dominate the federal government and dictate the laws of the South. Thus, when Lincoln emerged victorious over three other candidates in the presidential election, the Southern states took action.

Only five weeks after Lincoln’s election, South Carolina became the first state to secede, or separate, from America. By February 1861, as Lincoln was boarding his secret train, six more states followed South Carolina’s example — Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas — and the president-elect had a constitutional crisis on his hands. Were states allowed to just walk away from America and create a new country? Should the North use the military to force the South to come back into the Union?

Before Lincoln could take the oath of office and begin to answer these questions, the seven seceded states officially declared themselves a separate country: the Confederate States of America. The Confederate Constitution specifically protected slavery and gave more power to each individual Confederate state at the expense of its central government. (Otherwise, the Confederate Constitution was a close copy of the 1787 American Constitution, including most of the Bill of Rights). As Lincoln assumed office, everyone waited to see if the remaining slave states — Arkansas, Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia — would join the Confederacy or would stay loyal to the Union.

On April 12, 1861, the wait was over. Soldiers in the Confederate Army bombed Fort Sumter, a Union held fort that controlled access to Charleston, South Carolina, the second largest Southern city after New Orleans. Two days later, Lincoln called for 75,000 militia to fortify the U.S. Regular Army, which then consisted of only 16,000 officers and soldiers. Viewing Lincoln’s expansion of the Army as a direct threat, four more slave-holding states — Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Arkansas — seceded and joined the Confederacy.

By July, just three months later, a Union Army 35,000 strong marched through Washington, D.C., and passed cheering crowds waving American flags on its way to invade the Confederacy and capture its capital of Richmond, Virginia. Standing between the Union Army of new recruits and the rebel capital in Richmond only 100 miles away was the Confederate Army, which had seized the strategic rail yards in Manassas, Virginia. As the Union Army marched south from Washington, D.C., the stage was set for the first battle of the Civil War: The Battle of Bull Run (called The Battle of Manassas by the Confederacy, which named battles after the nearest town while the Union named battles after nearby rivers).

Manassas was still close enough to Washington that senators and their wives, as well as other well-to-do Washingtonians, rushed to the scene to be present when the Union Army crushed the rebel Confederates. However, the Confederate Army bested the untrained, raw recruits of the Union Army at Bull Run and sent the Army, as well as the senators, scrambling back into Washington, D.C., in complete disarray. As Lincoln watched the Union Army retreat into the capital, he realized that this was not going to be an easy victory. Lincoln drastically increased the Union Army again, this time calling for 500,000 volunteers.

Lincoln had been president for only four months when the Union Army was defeated at the Battle of Bull Run. Like the doubts raised by his overnight secret train, this first Union loss led many in both the North and South to question whether this lanky, bewhiskered man with a funny hat from a small town in Illinois could save the Union. It had only been 85 years since America had declared independence from the British Empire and 74 years since the writing of the American Constitution. Could a man born in a log cabin really put the world’s largest republic back together again?