Young Historian: Victory or Death

Young Historian: Victory or Death

November 5, 2024By KELI HOLT

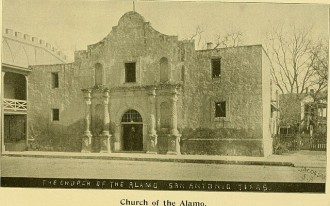

The remaining survivors crouched in the corner of the chapel, struggling to see through the gun smoke. Then came the boom of their own cannons firing at the church doors that separated them from their attackers. Davey Crockett looked at William Travis, commander of the Alamo garrison of Texas soldiers, wondering if their plea for reinforcements would be answered. Travis had signed his letter to the Texas Army with the pledge of “Victory or Death.” With each blast from the Mexican Army, death inched closer.

The events that eventually led to the battle began more than 30 years earlier. In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory from the French Emperor Napoleon, who had finally given up his dreams of recreating the French Empire in the Americas. Jefferson’s purchase more than doubled the size of America and included not only modern Louisiana but also all of the Midwest up to Canada and as far west as Idaho and parts of New Mexico.

Westward expansion, however, brought Americans much closer to various Native nations and to the Spanish who controlled the American Southwest. In 1804, Texas, New Mexico and California were the northernmost parts of the Spanish Empire. Spain built military outposts from the Gulf of California to the Gulf of Mexico to discourage raids by nomadic Native tribes and to keep the British and Americans away from its lucrative silver mines in Spanish Mexico. Spain also banned all foreign trade in an attempt to keep guns, horses and Western technology out of the hands of the Native tribes it sought to control. Due to these harsh policies and the poverty they created, few Spanish settlers moved to New Mexico, California or Texas.

By 1812, as America was battling Britain for the second time in 30 years, Mexican rebels were fighting for their own independence from Spain. In 1821, Mexico became an independent republic free from Spanish rule. Texas, New Mexico and California were now controlled by an independent Mexico City. The Native nations in Spanish America had been alternatively fighting and making peace with the Spanish for 300 years in an endless cycle of raiding, reprisals and temporary times of peace. As Mexico threw off Spanish rule, Mexico City inherited this violent frontier.

Initially, both Mexico and some Native nations welcomed American traders and settlers. After all, it had been the Spanish that nomadic tribes like the Navajo, Comanche and Utes had been fighting for centuries. American traders supplied them with the weapons, technology and animals that Spain had refused to sell. The new government in Mexico even created the Santa Fe Trail to increase trade with America.

In the 1820s, the American Stephen Austin made an agreement with the Mexican government to settle thousands of Americans in Mexican Texas. In return for large land grants, averaging 4,000 acres, American settlers had to take an oath of loyalty to Mexico and help bring peace to Texas, which had become more violent during the wars for Mexican independence.

While the initial wave of American migrants to Texas came in legally, thousands of Americans crossed into eastern Texas illegally with no intention of being loyal to Mexico City. These immigrants also brought large numbers of slaves with them as the soil of eastern Texas was perfect for growing cotton. Soon, these illegal squatters arrived in such numbers to worry Mexico City, which tried to assert more control over Texas.

As Mexico tried to make Texas more Mexican, Americans worked to make Texas more American. American settlers in Texas were particularly concerned that Mexico would enforce its prohibition on slavery, which had gone unenforced for decades. When Antonio López de Santa Anna overthrew the Mexican government in 1835 and made himself dictator, the Americans in Texas decided to act.

In 1835, Santa Anna sent his soldiers to Gonzales, Texas, (a small town near San Antonio) to retrieve a cannon that was used to defend against raids. A small band of Texans fired upon the Mexican soldiers, beginning the Texas Revolution. The rebels referred to this as their “Lexington and Concord” (the battles that began the American Revolution) and even drafted a Declaration of Independence from Mexico equating Santa Anna with King George III.

Santa Anna ordered his troops west, and a small contingent of the Texas Army under command of 26-year-old William Travis took refuge in the abandoned mission called the Alamo. As the Mexican Army approached, Travis sent out letters pleading for reinforcements. However, Sam Houston, the commander of the Texas Army, ordered Travis and his 200 soldiers to evacuate to East Texas. Travis ignored the command, and the Mexican Army surrounded the Alamo.

Ordered to attack, the Mexican Army used ladders to scale the walls, taking enormous casualties at the hands of the Texans inside. However, their sheer numbers allowed the Mexicans to overwhelm the mission and trap the remaining survivors. Using the rebels’ own cannons, the Mexican Army blasted holes in the church doors and in hand-to-hand combat killed every Texan inside. Any survivors were executed the next day.

The women and children of the Alamo defenders fled to eastern Texas. Santa Anna hoped their tales of horror would end the rebellion. Instead, the Texans advertised in America for volunteers to fight Santa Anna. These volunteers were promised 800 acres of land in return for their services. A few months later these volunteers forced Sam Houston to fight Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. The American recruits and Texans exacted a bloody reprisal upon the Mexican Army for the slaughter of the Alamo defenders. Santa Anna himself was captured and forced to give up Mexican claims to Texas.

From 1836 until 1845, Texas functioned as an independent country, albeit always under threat of Mexican invasion. In late 1845, the lame duck President John Tyler pushed Texas annexation through Congress with a simple majority vote. While cries of “Remember the Alamo” helped make Texas a state, its admission as a slave state deepened the sectional divide between the North and South. “Victory or Death” would haunt another generation of Americans in the Civil War.